The North-South Powerplay and how it affects the creation of ResTech

- Rohan Pai

- Jun 12, 2025

- 9 min read

Nandini Jiva, Rohan Pai

In 2015, in the aftermath of regional conflicts in Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq, approximately 1.3 million people migrated in the hope of better living conditions to member states of the European Union, UK, Norway and Switzerland. The resulting refugee crisis led to stricter legislation for asylum-seekers, propping up formidable enclosures such as the new European Border and Coast Guard (EBCGA–Frontex) that was supported by a whopping 245 million euros in budget allocations.

Policy efforts notwithstanding, the crisis also witnessed resurgent community action toward integration of refugees in destination countries across the EU. Community action emerged organically to real and immediate needs of refugees, aimed at fulfilling critical social functions such as legal aid, asylum documentation, network connectivity, shelter and healthcare. Such solutions were built using novel approaches that leveraged refugees’ access to mobile phones and internet, providing people on the move with essential information as demonstrated by initiatives like InfoAid and RefAid.

These community-oriented technology efforts prompted us to uncover further the range of initiatives that seek to address the essential needs of people on the move - what we refer to as ResTech. We noticed how these often invisible but critical technologies that mediate migration sit outside the institutional arrangements built by nation states and multilateral entities. Usually led by migrant rights organisations, civil society and community volunteers, these ResTech initiatives are integral applications that respond to the dynamic impulses of people on the move—focused on safety and integration during conflict.

Our research on ResTech found that they are often diffused across a variety of actors (businesses, citizen groups and civil society organisations), adaptable to people’s needs, and rooted in community trust. They emerge from necessity - whether through platforms providing secure language translation services, volunteer-led job-matching algorithms, or peer-to-peer skill-sharing applications. Despite their promising functions, ResTech initiatives remain few and far between, often flailing for want of funding, poor technology capabilities and even regional policy challenges.

These problems are further exacerbated within Global South countries, where conditions for the operation of ResTech are far from favourable, inherently privileging initiatives that are in the Global North. Recognising that these disparities have inevitable implications for the welfare of people on the move, it becomes crucial to identify, locate and examine the emerging ResTech initiatives and provide necessary safeguards (financial, social and policy) to ensure their continued operation. The current blog is but an attempt to present nascent insights on how these initiatives differ across the Global North and Global South, based on analysis derived from our live repository of ResTech that documents 50 such initiatives. As far as our categorisation is concerned, the Global North encapsulates the regions of the USA, EU, UK, and Oceania, and the Global South includes the Middle East-North Africa corridor, South Asia, parts of the Americas—Mexico, Central and South, as well as Africa.

Examining power and situating ResTech

In a post-colonial world, power asymmetries have manifested through narratives that bifurcate regions into “civilised” or “primitive”, “west” and “east”, “developed” and developing”, and refer to a “clash of civilisations.” Even the development of international law continues to reinforce this power asymmetry, affirming a North-South divide, calling on the Global North to maintain an ostensibly rules-based international order.

In the context of migration, this power asymmetry has been leveraged by high-resourced ‘destination’ countries through incentives (in the form of visas, access to trade markets, or development support, financial or otherwise) that restrict irregular migration towards their borders from Global South ‘transit’ and ‘origin’ countries. Migration diplomacy of this kind leads to negative consequences for migrants, limiting their freedom of movement and ability to seek safety in preferred destination countries.

Within such an environment, ResTech provides a community-led alternative for migrants to resist oppressive institutional structures and creates a resilient pathway for integration. However, based on our analysis, we noticed how these community-led modalities of resistance see higher effectiveness within high-resourced ‘destination’ countries in the Global North.

Our insights have demonstrated, in many ways, that there is an ever-present North-South differential that distinguishes how services are deployed. The following sections provide a deeper analysis of data from our taxonomy of ResTech, and help us uncover how conditions for technology development within crisis settings differ across regions in a post-colonial world.

Building a taxonomy and collating our insights

The impetus to build a taxonomy came from the need to identify and spotlight ResTech, and distil attributes of technologies that contribute to the creation of migrant-sensitive digital systems. In the course of our exploration, we uncovered facets of ResTech through three buckets: general information about ResTech, its technological attributes, compliance with privacy laws, and modes of funding. We used these buckets to draw insights into certain pivotal realities of building and deploying ResTech.

Through the process of this insight-building, we attempted to find variances in Global North and Global South contexts through the following parameters:

proximity to funding channels,

access to mature baseline technology and facilities, and

law and policy landscape that governs technology development.

By observing the emerging patterns across these parameters, we have evaluated what factors contribute to the ability of Global North-based ResTech initiatives to build sophisticated technology.

Funding channels

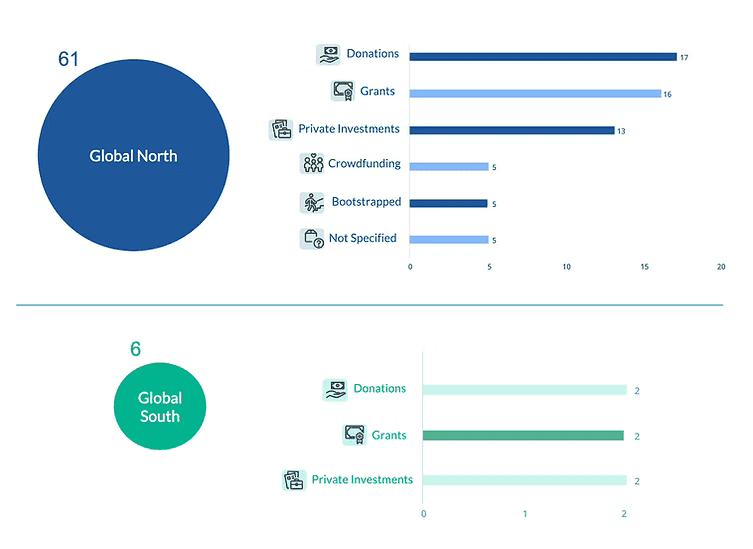

When it comes to funding, ResTech across the Global North and Global South are highly dependent on donations, grants and private investments to sustain themselves as depicted in Figure 1 below. It can be argued that the predominance of public debates on excesses of migration policy promotes counter-innovation through ResTech initiatives in the Global North regions - for example, in 2015, the European Commission and its 28 EU Member States had allocated €4.4 billion in response to the conflict in Syria and its neighbouring countries. Only 30% of this amount was specifically assigned for humanitarian assistance. Within such an environment, ResTech creators in the Global North remained incentivised to build technologies for migration support and fill emerging gaps in service provision. This was a common starting point for many who developed initiatives during the 2015 crisis, as stated by ResTech builders during our interviews with them. In contrast, the relatively low availability of humanitarian aid and assistance in the Global South creates uncertainty about support for ResTech initiatives, compelling reliance on private investments and individual donors to build a similar ecosystem.

Access to Technology

The reinforcement of power dynamics through access to advanced technology significantly shapes the resources available to Global North countries in developing platforms that aid and support migrants. A simple metric we used to calculate the difference was to compare where and by whom technologies were developed, and where it was eventually deployed. Our findings, as shown in Figure 2 below, reveal that 73% of the ResTech deployed in the Global North is also developed there. In contrast, only 40% of the technologies deployed in the Global South are developed there.

The need for ResTech deployed in the Global South to be supported by a Global North arm for technical support reflects how access to advanced technological capabilities is a critical factor in sustaining digital systems without the support of state and multilateral instruments.

Policy, law and regulatory landscape

ResTech originating in the Global North are often bound by a mature policy, law and regulatory landscape to safeguard users from privacy infringements that could potentially emerge from data collection and processing. In our taxonomy, we use the privacy principles laid down under the GDPR as a benchmark to measure compliance with such norms.

Based on our findings, Figure 3 below demonstrates that ResTech based out of Global North jurisdictions are compliant with GDPR to a large extent, but in many instances information on privacy policies was also unavailable - indicating the ad-hoc, and often impulsive nature of ResTech that bridge urgent gaps in service provision during conflict and emergencies. On the other hand, for ResTech situated in the Global South, there is minimal information available in the public domain about their privacy compliance status - often due to outdated or wholly absent privacy regulations.

However, it is important to caveat our construction of data rights. Contextualising ResTech data governance through merely these parameters often overlooks the communal nature of ResTech operations. Through examples of ResTech like Āhau—a shared cultural database for whanau-based communities around the world - it becomes evident that data rights within dominant privacy constructs such as the GDPR are inherently individualistic, with a superfluous focus on individual liberties. Such an approach is deficient in involving communities in decisions about how data is collected, where data is stored, and who it is shared with - aspects that initiatives like Āhau aim to correct.

It is essential to reposition our thinking through the lens of collective data rights: whether in the design of technology, providing grievance redressal mechanisms for communities, and furnishing details on the kind of information being processed by the systems in question. Therefore, looking at data governance through the lens of the GDPR is a good starting point, but it is an inadequate rubric. This part of our analysis requires further inquiry through frameworks that interrogate collective rights and justice around data, which have the potential to deliver migrants with agency over a broad range of technology use-cases.

Limitations to our inferences

ResTech is usually built as a consequence of a crisis, and its response looks different when one situates it in a Global North, usually destination countries, as opposed to a Global South, usually origin countries. Given that our discovery process for ResTech relied heavily on secondary and desk research, systems that feature in our taxonomy are those that can advertise in media and communication channels or set up and maintain websites online. Additionally, building technologies for migrants in the Global North can be correlated with integration efforts—due to the constant movement of people into these territories. These efforts are usually underpinned by an aspiration for long-term operations, a privilege missing for ad-hoc efforts that emerge during conflict and emergency settings, or by efforts in the Global South that do not have access to funding. Hence, a complete analysis of the ResTech ecosystem cannot be arrived at without primary research and deeper inquiries into technology efforts that exist on-ground - a feature that our repository is currently unable to speak to.

Additionally, the framing of the North-South divide is an oversimplification in a post-colonial, globalised world where geopolitics is not merely a result of a coloniser-colonised relationship. Scholars argue that the term “Global South” can fall short of the idiosyncrasies of the region. The framing itself embeds reductionist and folkloric nuances of the Global South, and while it supports the decolonising of narratives, it must not be taken too literally in its construction. The Global South as a dynamic construct is crucial to bring out the plural entity that it is, aided by the power dynamics at play within this umbrella term—technological advancements pioneered by China and India, the introduction of safety and privacy frameworks in Africa, to name a few. Multipolarity within the term Global South is manifold: it swings between varying geopolitical stances that countries take that cannot be encompassed within the term. Therefore, it becomes crucial to apply this limitation as a lens when clustering Global South countries as possessing the same degree of negotiating power in the geopolitics of ResTech.

The way forward: Overhauling the narrative

As we have conceptualised and observed in multiple cases, ResTech is capable of creating rights-preserving and equitable ecosystems through community-oriented innovation, and it is critical to support these efforts to create and sustain these systems alongside institutional migration infrastructure. This would also be a valuable exercise in centering the development of technologies within the lived experiences of people on the move.

Through our framing of ResTech, we have reimagined how technology design and deployment in the migration ecosystem can actively respond to the needs of people on the move. In our attempt to analyse the role of these initiatives in the migration ecosystem, we have developed an understanding of how these digital platforms are created, the incentives that help sustain their operations and why they serve as strong alternatives to existing infrastructure deployed by state, multilateral and commercial actors. However, inadequacies in community involvement, participatory data governance, and the extent of transparency in system architecture still hinder certain ResTech initiatives from being migrant-sensitive and serving as systems of care.

As highlighted in the previous sections, most ResTech we found have originated in the EU and USA due to the high influx of migrants and refugees into Global North regions. This is supported by a mature policy landscape within these countries due to governments having to pay active attention towards managing migration; capabilities to build advanced technologies at low cost; accessibility to larger funding pools for those developing technologies in these regions (sometimes even through grants); and advanced data protection and privacy regulations for handling sensitive data. However, it’s important to acknowledge that these conditions have also led to the creation of institutional migration control and surveillance infrastructure that is often discriminatory and exploitative through its targeting of vulnerable communities at the borders.

To bring forth a migrant lens in technology, governments and policymakers need to recognise the positive impacts of migration within their economies, and build narratives to incentivise technology development to support it. Deployers need to acknowledge the ResTech principle framework, and consciously align development efforts to address unmet needs; capture prevailing harms that existing systems perpetuate; and create societal impact by enabling migrants to negotiate their journeys. Finally, champions of ResTech need to raise awareness about funding requirements for these initiatives and assist in building capacities within Global South economies to incubate such efforts.

Our vision for ResTech is to see it as a promise for greater migrant agency, to resist the creation of building systems that control migration, and for people on the move to realise their autonomy through this approach to technology development. However, achieving this would require grappling with the existing differences between ResTech efforts in the Global North and South, and acknowledging that region-specific complications are prevalent. Strategies for developing the ResTech ecosystem will therefore require placing these efforts within geopolitical realities and evaluating strategies for sustainability that are considerate of individual migration contexts.

Comments