Digital integrations across porous borders : Nepalese migrants in India

by Poorvi Yerrapureddy, Amrita Nanda

and Sakhi Shah

Migration Stage:

DEVELOPMENT

INTEGRATION

This case study explores the integration of Nepalese migrants in India, focusing on the role of digital public infrastructure. It examines the challenges migrants face in accessing services and the impact of digital systems on their socio-economic inclusion. This study draws from field research, stakeholder interviews, and policy analysis, to provide insights and recommendations for enhancing the digital integration and welfare of Nepalese migrants.

This report was produced by Aapti Institute in partnership with the Robert Bosch Stiftung GmbH

Executive Summary

Integration and Accessibility: Evaluating the Impact of India’s Digital Systems for Migrants

-

Interaction with Aadhaar and Integration with DPI: Welfare and offline inclusivity

-

Digital Payment Adoption: The Impact on Migrant Remittances

From Promise to Practice: The Effectiveness of Integration Policies for Nepali Migrants

-

Invisibilisation of Nepali workers: How does the lack of policy frameworks exacerbate the vulnerability of Nepali migrants?

-

From Design to Reality: Evaluating the Real Benefits of Aadhaar for Nepali Migrants

Development to Adoption: Low Uptake of Migration Support Technologies Among Nepali Migrants

Overview

Aadhaar is a biometric identification system implemented by the Government of India. Launched in 2009, Aadhaar aims to provide a unique identification number to every resident of India, addressing challenges related to identity verification, efficient public service delivery, and inclusive governance. The Aadhaar system utilises biometric and demographic data to create a unique digital identity for individuals.

Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission[2]

The Government of India launched the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM) to promote digitization in healthcare and establish an open interoperable digital health ecosystem. The mission aims to establish common health data standards and develop core modules such as health facility registries and healthcare professional databases for seamless data sharing among different digital health systems.

Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI)[3]

A set of shared digital systems which are secure and interoperable, built on open standards, and specifications to deliver and provide equitable access to public and/ or private services at societal scale and are governed by enabling rules to drive development, inclusion, innovation, trust, and competition and respect human rights and fundamental freedoms.

United Payments Interface[4]

India’s fast payments solution that powers multiple bank accounts into a single mobile application (of any participating bank), merging several banking features, seamless fund routing, and merchant payments into one hood. It also facilitates “Peer to Peer” payments.

Mixed Migration[5]

Which seeks to capture the intertwined and multifaceted drivers of movement of all people, regardless of status. A mixed migration lens helps to enlarge the protection space for people on the move who may not qualify for refugee status, or may not have left their countries for reasons laid out in the 1951 Refugee Convention, or regional refugee instruments, but who still might have felt compelled to leave for a combination of interrelated factors, including economic, political, social and religious or ethnic ones.

Definitions

Executive Summary

Human migration is not composed of a singular event or experience but a complex process from initial movement and subsequent integration into the host region. In this regard, understanding digital systems in migration requires also a deep exploration of the infrastructure that follows people on the move into newer lives. More often than not, the systems relied on in the long-term, multi-faceted process of ‘integration’ are experienced differently by migrants. This integration is crucial.It determines the migrant’s ability to access employment, healthcare, education, and social services, and frames what ‘success’ might look like for people on the move. Without proper integration, migrants remain on the margins of social, economic and cultural assimilation, creating great room for vulnerability long after a journey has been undertaken.

Systems deployed toward integration efforts remain lesser understood. While many countries have established robust mechanisms to manage the flow of migrants across their borders, it is crucial to unpack existing and necessary support for integration as well. Prevailing lacunas in integration systems can create significant challenges for migrants who struggle to navigate unfamiliar systems and face barriers in accessing essential services. Addressing these gaps is crucial for ensuring migrants are supported in their new country, allowing them to integrate into the community.

To better understand this segment of migration, this report selects a case of voluntary migration, a corridor that is state-sanctioned and holds purported political will in encouraging the pathway. In the migration corridor between Nepal and India, migration is driven by choice and aspiration. Collaborative efforts from both nations work to facilitate this flow of people.

Despite willingness and policy support, the lived process of assimilating into a new society remains fraught with challenges for the migrants. They face obstacles such as cultural differences, language barriers, and unfamiliar administrative processes. In the digital age, technology plays a pivotal role in this integration; providing tools that can bridge gaps in language, information, and access to services. However, for these tools to be truly effective, they must be designed with an understanding of the needs and experiences of migrants, ensuring that digital platforms are not only accessible but also culturally and contextually relevant.

Digital platforms can offer migrants essential information about their rights, available services, and integration processes in their native languages, making it easier for them to adapt. This is where DPI can play a transformative role. By providing streamlined access to essential services like identification, banking, healthcare, and employment information through digital platforms, DPI can bridge the integration gap. For instance, a migrant arriving in India can quickly obtain an Aadhaar card and open a bank account if the DPI is user-friendly and accessible, thus enabling them to establish a legal identity and financial stability. Such integration tools are vital for helping migrants navigate their new environment.

The journey of migration is a brief phase compared to the prolonged period of integration that follows - this is the stage that seeks to fulfill the purpose and aspiration of migration. Upon arrival, the ability to access and utilise digital public infrastructure becomes critical for migrants. Having a valid ID, such as the Aadhaar card in India, is essential for accessing services that are pivotal to daily life. This ID serves as a gateway to open bank accounts, secure employment, obtain SIM cards, and access healthcare services. For instance, without an Aadhaar card, a migrant worker may struggle to receive wages through formal banking channels, limiting their financial inclusion and increasing their reliance on informal and potentially exploitative systems.

Seamless digital payment systems enable migrants to send remittances back home efficiently and affordably, supporting their families and communities. The ease of transferring money can significantly impact a migrant’s ability to manage their finances. Furthermore, digital integration aids in creating a sense of belonging and stability, reducing the uncertainty and isolation that often accompany migration. Access to digital services ensures that migrants are not left on the periphery but are integrated into the socio-economic fabric of the host country. In a country with robust digital public infrastructure, there is potential to envision meaningful, responsible and migrant-centric integration through digital mediation.

This case report studies the existing and potential impact of digital infrastructure for migrating communities, with specific focus on Nepalese migrants in India. As part of the authorship’s larger project and effort to unpack digital systems, data infrastructure and data governance in migration - this report explores the stage of integration, its reliance on and degree of technological mediation.

We extend our sincere gratitude to the independent anonymous researcher who contributed significantly to our fieldwork and authored several sections of this report, whose insights and dedication have been invaluable to this work.

Introduction

Background

The history of migrations from Nepal to India spans many decades. While the number of Nepalese citizens residing in India vary, it is safe to assume that the figure is anywhere from 1.8 million to 5 million[6] and there are seasonal variations in these numbers. Censuses in Nepal suggest that around 80% of Nepal’s absentee population[7] resides in India, though numbers may have changed in the recent past. Nepal and India share an open border, courtesy of the 1950 Peace and Friendship treaty[8] between the countries which has facilitated an unrestricted movement of people across the border.

Academicians have engaged with migration from India and Nepal from both sides of the border to better understand the impetus to move, and the conditions of migrants in India. The primary historical reason for migration has been economic,[9] driven by poor conditions in Nepal. However, recent studies provide an additionally nuanced understanding, highlighting factors such as “modernity and masculinity”, where young Nepali men view moving to India as a “rite of passage”.[10]

Mixed migration involves individuals with different legal statuses who encounter various vulnerable situations. Although they travel along the same migration routes and use similar forms of transportation, their reasons for migrating differ significantly. Mixed migration[11] underscores the intertwined and multifaceted drivers that influence the movement of all people, regardless of their status.

The experience of Nepalese migrants in India is defined by their itinerant nature,[12] and their existence has been called “liminal” as they are not treated as foreigners,[13] nor as citizens. This liminal status exposes them to vulnerabilities and fails to establish channels for accountability.

The liminality in a digital context refers to the transitional and often ambiguous state migrants occupy within digital systems, which can exacerbate vulnerabilities and hinder accountability. Broadening our understanding of these complex motivations and addressing the digital liminality is crucial for better governing and supporting migrants.

India’s digital public infrastructure (DPI) enables Nepali residents to apply for digital identity (Aadhaar) and engage in digital transactions through the unified payments interface (UPI). This research demonstrates that despite the prevalence of DPI, Nepalese citizens suffer precarity, and lack of integration in India, and continue to exist in the informal economy. The promises of the Peace and Friendship treaty, and the ease of movement is not addressed in the technological design and deployment. This dissonance between the promise of openness of the border and the reality of migration between India and Nepal is the core justification for the selection of this case study.

This work examines Nepalese migration in India, exploring how migrants access services through new technological systems that, while designed to promote inclusion and enablement, can also act as instruments of alienation. This analysis is framed within the broader context of migration toward integration.

In the following sections, the authors elaborate on the methodology of the research, and provide a detailed background of Nepalese migration in India. The case study aims to highlight the challenges and opportunities Nepalese migrants face in accessing and utilising technological systems and DPI. It charts a way forward through recommendations emphasising the need for inclusive and adaptive frameworks alongside community engagement to ensure successful integration and reduce alienation. This exploration is anchored in understanding how identity plays a role in allowing access to welfare services and making integration easier for Nepalese migrants.

Methodology

This study adopted an evidence-based, bottom-up approach to better understand the impact of digital systems on Nepalese migrants and the extent of their interactions. The study is anchored on multiple forms of research that overlap and reinforce each other.

From our research we have theorised that there are primarily three stages (sometimes evolutionary) of migration; crisis, development and integration. The Nepalese migrants are currently at the stage of development where there is an emerging technology landscape for surveillance and inclusion along with certain provisions for legal identity and social inclusion.

SECONDARY

Desk Research

PRIMARY

Expert Interviews

PRIMARY

Field Exploration

AUGMENTING

Analysis

Desk Research

This work relies on an extensive review of academic and grey literature to better understand the history of the Nepalese migration to India, its drivers, the socio-political context, and most critically, the intersection with digital systems. For this, sources such as academic research papers, government documents, treaties and news/media reports have been referenced. Reports by national and international non-profits have also been consulted. This enabled reading and understanding of the existing landscape, identifying gaps and further areas of exploration at the intersection of migration and technology focused on the lived experiences of Nepalese migrants. Despite the vastness of literature referred in this work (bibliography annexed) , it is important to note the immense gap in the literature on the interactions of migrants with technological infrastructure in India.ven though India’s DPI is an example that is being studied and referenced globally, its own examination in the context of a foreign population in its own borders is missing. Therefore, this case study aims to plug a critical gap and create new knowledge on the intersection between migrant rights and digital public infrastructure in India.

Expert Interviews

To address the gaps in literature, this study relied on expert interviews to untangle lived experiences of Nepalese migrants at an aggregated level. The ecosystem is largely made up of civil society organisations focused on the well-being of Nepalese migrants, especially from the lens of labour and the precarities around informality. Expert interviews also included community actors, who work on issues of social security to add perspective on ideas of inclusion and access.

Primary Field Research

Given the research limitations in understanding the experiences of Nepalese migrants, particularly from a digital lens; we conducted 16 semi-structured field interviews and 4 Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) across 2 sites in India [Bangalore and Delhi] in order to answer the following questions:

-

Which digital systems and data infrastructures do Nepalese migrants interact with?

-

Who are the stakeholders involved, what is the purpose of these infrastructures, and what are the intended benefits?

-

What are the experiences (and breakdowns) of Nepalese migrants who access and interact with such digital systems and data infrastructures?

-

What alternate systems of resilience can enable the realisation of intended benefits, the potential of community and civil society, and reimagining impact and value back to Nepalese migrants anchored in their digital and data interactions?

Through a mixed methodology and its resultant insights, the following case study explores the digital systems and data infrastructures that Nepalese migrants interact with, identifying the stakeholders involved, the purpose of these infrastructures, and the intended benefits. It delves into the experiences and challenges faced by Nepalese migrants when accessing and using these digital systems. Additionally, the authors examine alternate systems of resilience that can enable the realisation of intended benefits, the potential of community and civil society, and the reimagining of impact and value for Nepalese migrants anchored in their digital and data interactions.

Complications

In the dynamic journey for Nepalese migrants - from departure to arrival and integration - the digital landscape becomes a site for numerous challenges and opportunities. Analysing the effectiveness of the digital ecosystem, particularly the ID system, healthcare along with financial systems, pertaining to the Nepalese migrants is vital in understanding their digital interactions. From Aadhaar to UPI, there exists an intricate web of barriers, advantages, and opportunities that define their digital journey. This section delves into the complexities that define their interaction with the digital public infrastructure and the conundrum of technological promise versus practical integration, by unravelling the interplay between existing technologies and the exclusionary forces.

Takeaways

What policymakers need to do

-

DPI is crucial for accessing services in India. To integrate migrants effectively, the Indo-Nepal Treaty must align with DPI. Policymakers must integrate DPI into their efforts to realise the treaty’s goals.

-

Nepalese migrants lack access to both Indian and Nepalese welfare schemes, leaving them vulnerable in both countries. Nepali policies exclude migrants in India from benefits given to other overseas workers, while Indian welfare schemes are limited to citizens.

-

Current policies do not fully address the socio-cultural assimilation of migrants or their integration into DPI systems. While Aadhaar aims to provide access to services, institutional barriers limit its effectiveness. Integrating DPI can enhance socio-cultural assimilation and more effectively meet migrants’ needs.

Integration and Accessibility: Evaluating the Impact of India’s Digital Systems for Migrants

India’s digital public infrastructure is currently not well-suited to accommodate the needs of migrants, particularly those from Nepal. Despite the widespread adoption and benefits of systems like Aadhaar, significant barriers exist that prevent migrants from fully accessing and utilising these services. The following section will explore the inherent challenges within the DPI, highlighting the systemic obstacles that impede the integration and effective service delivery for Nepalese migrants in India.

The Aadhaar system is a cornerstone of identity verification in Indian digital infrastructure that provides individuals with access to various services in India, yet the path to acquiring an Aadhaar is laden with obstacles. In the realm of digital transactions, UPI emerges as a pivotal tool for financial interactions, yet its limitations for remittances and the necessity of an Indian bank account poses some hurdles for Nepalese migrants. Nepalese migrants tread a delicate balance between opportunity and exclusion in the digital realm. In this exploration of the current state of digital public infrastructure for Nepalese migrants in India, we unravel the complexities that define their digital journey.

Interaction with Aadhaar and Integration with DPI: Welfare and offline inclusivity

The Government of India enacted the Aadhaar (Targeted Delivery of Financial and other Subsidies, Benefits, and Services) Act,[34] 2016 to provide identification to every resident of the country against submission of demographic and biometric information. Over time, the usage of Aadhaar has primarily become two-pronged - a proof of identity and proof of address, becoming a preferable document for banking services[35] among others.

The significance of an Aadhaar card in India cannot be overstated, it serves as a linchpin for accessing numerous services.[36] There are numerous direct and ancillary benefits that are available through an Aadhaar card, the ancillary benefits include the procurement of a SIM card, and is crucial for fulfilling Know Your Customer (KYC) requirements, which are mandatory for opening bank accounts. This, in turn, enables financial inclusion and economic participation.

Nepalese citizens meeting the residence requirement of 182 days are eligible for Aadhaar enrolment under UIDAI,[37] which provides specific documentation requirements and requires foreign residents to complete an enrolment form.[38]

Nepalese migrants in India face significant challenges in obtaining Aadhaar cards[39] despite their legal eligibility. Empirical evidence from our fieldwork reveals substantial impediments that hinder their access to this essential identification document. One of the primary challenges these migrants encounter relates to discrepancies in recording age and date of birth. This issue stems from the incongruity between the Nepalese calendar, which is based on the Bikram Sambat system, and the Gregorian calendar used in India.

The lack of an offline mechanism for converting dates between these two systems exacerbates the difficulty, rendering the Aadhaar application process convoluted for many Nepalese individuals, despite the Indian government’s assurance of Aadhaar accessibility[40] for Nepalese migrants. This deficiency highlights a critical gap in the implementation of what is ostensibly an inclusive policy. The procedural rigidity further compounds the problem, leaving many Nepalese migrants excluded from the benefits associated with Aadhaar.

There are inconsistent practices at enrolment centres due to the lack of clarity surrounding Aadhaar eligibility for migrants. While some centres issue Aadhaar cards to migrants based on their government-issued documentation, others turn them away due to uncertainty about these requirements.[41] This lack of uniformity creates distrust among applicants who are often incorrectly equated with illegal immigrants, further discouraging them from pursuing Aadhaar enrolment.

It is crucial for the Indian government to establish clear guidelines and provide training to Aadhaar enrolment centres on the eligibility of Nepalese migrants. By ensuring that Nepali migrants have access to Aadhaar cards, the government can promote their inclusion in India and prevent perpetuation of their socio-economic vulnerability.

Despite the promises embedded in the bilateral treaty and the theoretical inclusivity of the Aadhaar system, these migrants face substantial barriers in fully accessing the suite of digital services available through Aadhaar. The primary issue lies in the disparity between the government’s commitments and the on-ground realities, where infrastructural inadequacies and procedural hurdles persist. This exclusion leads to incomplete assimilation, as true integration into Indian society necessitates equitable access to healthcare.

While the Aadhaar system was envisioned as a tool for socio-economic inclusion, the lack of a conversion mechanism between the Nepalese and Gregorian calendars, as well as the inconsistent practices at enrolment centres, have created significant barriers for Nepali migrants in obtaining this essential document. This gap between policy and implementation not only marginalises Nepali migrants but also calls into question the efficacy of India’s digital public infrastructure in catering to resident foreigners. Bridging this gap requires targeted policy interventions and infrastructural enhancements to ensure that the promises of accessibility and inclusion are fulfilled.

Digital Integration vs. Welfare Access: The Healthcare Dichotomy for Nepalese Migrants

Navigating the healthcare system in India poses challenges for Nepalese migrants. Financial constraints often compel them to prefer government hospitals over private healthcare providers. Despite government hospitals offering more affordable services, these facilities are frequently overwhelmed. Additionally, language barriers and a lack of awareness about available health services exacerbate their difficulties.

Access to healthcare for Nepalese migrants is challenging, during our fieldwork, many migrants reported significant difficulties when seeking healthcare at both private and public hospitals.[42] The migrants we interviewed mentioned being required to present an Aadhaar card for identification, despite observing that citizens were not subjected to the same requirement.[43] This demonstrates exclusion at the most basic level for Nepalese migrants. Being asked to present an Aadhaar card as a prerequisite for healthcare access highlights a systemic barrier that exacerbates their vulnerabilities. Without this identification, migrants have been denied essential medical services, highlighting a disparity in treatment between them and Indian citizens; exemplifying the broader challenge Nepalese migrants face in securing their well-being and integration into society.

The Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi initiated the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY) scheme in 2018 designed to provide certain populations with subsidised health insurance rates. However, eligibility for this scheme is restricted to those in possession of a ration card. A significant barrier faced by the migrants for access to healthcare arises from the lack of a ration card. Unlike Indian citizens, Nepali migrants do not have official access to a ration card due to a ruling by the Himachal Pradesh High Court in the Mool Pravah Akhil Bharat Nepal Ekta Samaj and Anr v. State of Himachal Pradesh,[44] a matter that is currently awaiting final ruling from the Supreme Court. The protracted nature of this legal battle perpetuates uncertainty and impedes the migrants’ ability to benefit from the entitlements linked to ration cards.

The implications of this exclusion are far-reaching, particularly concerning access to essential services and welfare schemes. Consequently, Nepali migrants are effectively barred from accessing this crucial healthcare subsidy. This exclusion highlights the systemic challenges faced by migrants and brings forth the need for policy reforms to address their unique circumstances as resident foreigners.

In contrast to the ration card and PMJAY scheme, the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM) offers inclusivity for Nepali migrants. ABDM facilitates the issuance of an Ayushman Bharat Health Account (ABHA) number, which enables individuals to digitise their health data and records.[45] This digital integration enhances healthcare accessibility and continuity for migrants, providing them with a portable health information system. The ABHA number allows healthcare providers to access a migrant’s medical history, thereby improving the quality and efficiency of healthcare services rendered.[46]

Despite the advantages presented by the ABDM, the overarching exclusion from the ration card system and PMJAY scheme highlights a dichotomy in the accessibility of India’s welfare mechanisms. While digital health records offer some degree of inclusion, an inability to access subsidised healthcare and other benefits linked to the ration card remains an obstacle.

Digital Payment Adoption: The Impact on Migrant Remittances

The Indo-Nepalese remittance system serves as a critical financial conduit for many Nepalese families, with migrant workers in India sending substantial portions of their earnings back home. This section elaborates on the mechanisms of the Indo-Nepal remittance system and digital payment solutions to enhance the efficiency of cross-border financial transfers.

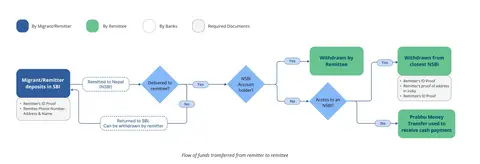

The Indo-Nepal Remittance Facility (INRF) Scheme is facilitated by the Reserve Bank of India; it has undergone significant enhancements to improve cross-border remittances between India and Nepal. This represents a transformative tool, particularly because it extends its utility to non-bank holders; individuals do not need to possess a bank account[47] in either India or Nepal to utilise these remittance services. The accessibility of such facilities is crucial, as it democratises financial transactions and allows migrants to send money to their families in Nepal with relative ease.

The only banks authorised to route remittance facilities are the State Bank of India (SBI) and Nepal SBI (NSBI), both public sector entities. This ensures a streamlined and regulated channel for financial transfers, leveraging existing DPI to facilitate these transactions. The robustness of the system enables the smooth operation of remittance services, providing a framework through which funds can be transferred securely and efficiently. Notably, the recent increase in the transaction ceiling[48] from ₹50,000 to ₹2 lakh and the removal of the cap on the number of remittances per year have expanded the scope and ease of remittance transactions.

The bilateral arrangements between banks and non-bank entities to handle cross-border transactions between India and Nepal remain outside the purview of the Indo-Nepal Remittance Facility Scheme[49] (INRF). The INRF Scheme exclusively relies on the National Electronic Funds Transfer ecosystem to manage remittances to Nepal. Consequently, all NEFT-enabled bank branches are already integrated into the scheme, ensuring a structured and regulated remittance pathway.

Despite the transformative nature of the remittance facility, concerns persist regarding the declining trend in the number of remittances in recent years.[50] This decline raises concerns about the underlying factors contributing to this trend. One primary concern is the migrants’ knowledge of the available databases and facilities. Many migrants may lack the necessary awareness or understanding of how to fully utilise the remittance services possibly stemming from inadequate dissemination of information or limited digital literacy.

Additionally, the reliance on only two banks for remittance services presents challenges in terms of accessibility and convenience. Migrants located in areas without easy access to SBI or NSBI branches may find it difficult to use these services, thereby hindering their ability to remit money to Nepal. The procedural complexities associated with using these facilities might deter some migrants from fully engaging with the system. Further, a complete reliance on NEFT for remittance under the INRF Scheme, while secure and regulated, may not be the most accessible method for all users.

Other than NEFT and walk-ins, UPI is one of the most important interfaces to transfer money domestically in India. Among Nepalese migrants who do have bank accounts in India, the adoption of digital payment platforms like UPI is prevalent, with PhonePe and Google Pay being the most commonly used applications.[51] Even respondents who do not directly use these apps themselves are aware of their usage by family members such as spouses or children, indicating a widespread familiarity and reliance on digital payment solutions within the migrant community.[52]

UPI’s real-time payment capabilities could revolutionise the remittance landscape by offering instant transfers, thereby enhancing the overall efficiency and user experience. The immediacy and simplicity of UPI could significantly streamline the remittance process for migrants, providing a seamless and cost-effective means of transferring funds. Despite its potential, UPI remains underutilised among migrants, particularly those from Nepal, due to its exclusive bank-to-bank transfer mechanism. This limitation is significant, given that a substantial portion of the Indo-Nepal migrant population remains unbanked.[53] Without access to bank accounts, these individuals are excluded from the benefits that UPI offers.

While the current system of INRF provides a regulated and secure pathway for remittances, the integration of UPI has potential to streamline and expedite the remittance process, offering a more user-friendly and accessible option for migrants. This can be done by expanding the guidelines of the INRF Scheme to include UPI could democratise access to remittance services, providing a faster and potentially cheaper alternative to NEFT.

In furtherance of this, the use case for UPI has been extended to Nepal, keeping in view the “Neighbourhood First” policy.[54] The RBI and the NRB have been actively exploring the utilisation of UPI to facilitate cross-border remittances[55] between India and Nepal. This move represents a step towards leveraging digital payment platforms to enhance cross-border financial transactions, potentially simplifying the remittance process for Nepalese migrants. and ultimately fostering greater financial integration between the two countries. However, the marginalisation of unbanked communities would persist even in the inclusion of UPI. This prompts a more fundamental question on the access to and impetus of digital infrastructure; how can we envision technological streamlining in tandem with offline challenges - to prevent the exacerbation of existing inequities. Section 5 explores the potential for UPI and other financial solutions to enhance the financial landscape for migrants.

From Promise to Practice: The Effectiveness of Integration Policies for Nepali Migrants

The promise of integration made by the Indo-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship envisions seamless assimilation of Nepalese migrants into the Indian socio-economic fabric. To refer to the aforementioned classification of migration stages, policies and digital systems look different and play different roles when oriented toward a ‘development’ or settling phase, and when oriented toward the ‘integration’ and assimilation phase. In the status quo,policies and technology systems for Nepalese migrants are largely development-oriented and do not allow for meaningful integration or realising migrant aspirations, as identified across the systems and areas of complications explicated in this section. Meaningful integration facilitates a socio-economic environment that enables migrants to build resilient, longitudinal and aspirational systems of social, economic and cultural growth. A prevailing reliance by Nepalese migrants upon informal employment and unorganised sectors highlights a concerning inaccessibility to the formal economy, reducing also their ability to contribute to skills, labour, innovation and entrepreneurship in the Indian economy. This remains the case for most migrants, despite the Indo-Nepal Treaty affordings certain rights to citizens in both countries including free movement across the borders, employment, and settlement. Despite eligibility for Aadhaar, bureaucratic challenges and lack of awareness impede their ability to obtain and utilise this crucial identification. This inadequacy results in the invisibilization of Nepalese migrants, hindering their access to banking, telecommunications, and government welfare schemes.

Thus, there is a need to think about this emergent dissonance - between political will and promise, and the lived reality or design of digital systems. How can digital systems in migration be meaningfully geared toward assimilation? The following section delves into the shortcomings that prevent the full realisation of the treaty’s promises for the socio-economic inclusion of Nepalese migrants in India, through an exploration of ‘integration’ as a mixed fabric - a composite of social, cultural, economic, experiential and lived negotiations.

Invisibilisation of Nepali workers: How does the lack of policy frameworks exacerbate the vulnerability of Nepali migrants?

The phenomenon of invisibilization of Nepali migrants is pervasive in both India and Nepal. This widespread invisibility[56] means that the socio-economic contributions and struggles of these migrants remain largely unacknowledged, exacerbating their vulnerabilities.

In India, Nepali migrants occupy a precarious position, despite their significant numbers and contributions to the informal economy, they cannot access welfare in the country.[57] Although they often hold Aadhaar cards as resident foreigners, they have a lack of access to welfare places them in a complex situation. The Aadhaar card is crucial for accessing various services and formal employment even though it does not confer any legal rights or protections typically associated with citizenship. The invisibilisation of Nepalese migrants in India has been manifesting through inadequate policy frameworks. Consequently, Nepali migrants are left in a liminal space—neither fully integrated into Indian society nor afforded the rights and benefits that come with formal recognition. This ambiguity further entrenches their invisibility.

The vulnerability is compounded by the legislative framework in Nepal. The Nepalese government’s policy does not recognize Nepalese working in India as part of the foreign employment sector.[58] This exclusion has significant ramifications, primarily, it means that Nepali migrants in India are ineligible for the benefits and protections that the Nepalese government provides to other migrant workers abroad. These benefits tend to include insurance schemes, welfare programs, and repatriation assistance, which are vital for safeguarding the well-being of migrant workers.[59] The lack of such recognition leaves Nepali migrants in India without a safety net, exacerbating their vulnerability.

The Migrant Workers’ Welfare Fund in Nepal offers crucial benefits, such as health insurance and financial support for injuries or accidents, to Nepali migrants.[60] This fund operates on contributions made by the migrants themselves, serving as a vital safety net for those working abroad. Labour permits are a prerequisite for accessing the Migrant Workers’ Welfare Fund.[59] As Nepali migrants in India are not provided with these permits, they are effectively excluded from the benefits of the fund. This exclusion leaves them without essential protections and support, increasing their vulnerability. The absence of labour permits thus creates a significant gap in the safety net for Nepali migrants in India, underscoring the need for policy revisions to extend these critical benefits to all Nepali workers abroad, irrespective of their destination.

The invisibilization of Nepali migrants operates on multiple levels. In India their access to social welfare and protections is limited reinforcing their status as a marginalised group within the informal economy. In Nepal, the legislative oversight means that these migrants are overlooked in national policies designed to support the diaspora. This dual neglect highlights a significant gap in both countries’ approaches to managing and supporting migrant labour.

From Design to Reality: Evaluating the Real Benefits of Aadhaar for Nepali Migrants

Nepali migrants in India have been integrated into the Aadhaar network, a supposed significant step toward formal recognition and inclusion within the Indian socio-economic framework. The residency requirement aims to ensure that migrants have established a significant presence in the country before accessing the benefits of the Aadhaar system. Once issued an Aadhaar card, migrants can theoretically avail themselves of a suite of digital services designed to enhance their integration and access to various social benefits and utilities.

The Aadhaar card serves as a gateway to a range of digital services, including banking, mobile phone connections, and various government welfare schemes for citizens. These services are designed to streamline processes, enhance accessibility, and ensure efficient delivery of benefits. Despite the potential advantages, one of the significant challenges is that not all Aadhaar cardholders can fully utilise these digital services.

The outcome indicators of any DPI must effectively demonstrate the system’s impact and efficiency.[62] These indicators aid in assessing whether the DPI is achieving its intended goals and delivering tangible benefits on the ground. Similar metrics can be utilised to gauge the effectiveness of Aadhaar and associated services. These include data on service uptake, offline infrastructure, and improvements in access to government schemes and financial services.

Development of robust outcome indicators and ensuring their consistent application will aid policymakers in identifying areas for improvement and make data-driven decisions to enhance the inclusivity and effectiveness of the DPI. This would not only validate the system’s performance but also guide future efforts to bridge the gap between policy and practice.

The benefits of the Aadhaar system are predominantly available only to Indian citizens, excluding resident foreigners, from accessing the full range of advantages associated with the Aadhaar card. This exclusion creates a significant gap in realising the integration promised by the Indo-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship, which aims to provide Nepali migrants with similar rights and opportunities as Indian citizens.

Nepalese migrants are currently integrated into the Aadhaar network, which provides them with a unique identification number, ostensibly facilitating their access to various services and benefits within India. When evaluating the utility of Aadhaar for these migrants, it is crucial to adopt a twofold perspective: examining both the primary/substantial benefits and the secondary/ancillary benefits.

The first-order or substantial benefits of Aadhaar are those directly related to government schemes and entitlements. These include access to social welfare programs, healthcare subsidies, and other governmental provisions that are designed to improve the socio-economic status of residents. In theory, Aadhaar should enable Nepalese migrants to seamlessly access these benefits, thereby ensuring their inclusion in the broader socio-economic framework of the country.

Despite the inherent utility of Aadhaar, the ultimate outcomes that migrants should be receiving through this system have largely eluded them. Institutional barriers prevent migrants from fully leveraging Aadhaar’s potential. As a result, the substantial benefits that Aadhaar is designed to provide are not reaching the migrant population.

On the other hand, the ancillary benefits of Aadhaar are more readily accessible to Nepalese migrants. These include the ability to open bank accounts, purchase SIM cards, and facilitate identity verification processes.[63] These benefits, while significant, represent only a fraction of the intended utility of Aadhaar. For many migrants, the ability to access basic financial and communication services marks an improvement in their quality of life, yet it falls short of the comprehensive support that Aadhaar is meant to provide.

The design of Aadhaar inherently holds the potential to be immensely useful to migrants by simplifying identity verification and facilitating access to numerous services. These benefits are essential for ensuring long-term stability and integration for migrants. This discrepancy arises due to systemic barriers and the partial implementation of Aadhaar’s potential benefits.

Migrants may manage to utilise ancillary benefits, the more transformative substantial benefits remain largely inaccessible. The gap between the design and the actual delivery of these benefits showcases a pressing need for policy reform and enhanced implementation strategies. Addressing this gap requires targeted interventions to ensure that substantial benefits are made genuinely accessible to this population. By doing so, the Aadhaar system can fulfil its potential to significantly improve the lives of Nepali migrants in India.

It is essential to consistently evaluate the impact of the Aadhaar system, ensuring it serves not only Indian citizens but also the migrant population effectively. Such measures would help in identifying gaps, driving policy improvements, and ultimately fostering a more inclusive environment for all Aadhaar cardholders.

To honour the treaty’s promise of integration, it is imperative to extend certain benefits to Nepali migrants holding Aadhaar cards. This extension should encompass not only the ancillary benefits like opening bank accounts and obtaining SIM cards but also the substantial benefits such as access to government welfare schemes, healthcare, and education. Ensuring that Nepali migrants can access these benefits would promote a more inclusive and supportive environment, aligning with the treaty’s intent.

The most significant constraint in achieving this integration is the inadequacy of the current offline infrastructure. Many government schemes and services require in-person verification and documentation processes, which can be cumbersome and inaccessible for migrants who often face language barriers, lack of awareness, and bureaucratic red tape. The offline infrastructure fails to fully support the seamless integration of Nepali migrants.

To address these challenges, there needs to be a concerted effort to enhance the offline infrastructure, making it more accessible and efficient for migrants. This could include setting up dedicated help centres, simplifying documentation processes. Additionally, increasing awareness about the rights and benefits available to Nepali migrants under the treaty can empower them to better navigate the system.

Development to Adoption: Low Uptake of Migration Support Technologies Among Nepali Migrants

One of the biggest challenges identified from the field research was the limited awareness and apprehension among many Nepalese migrants regarding the available technologies designed to aid them. Despite the development of certain technological tools specifically tailored to assist migrants in their journeys, the uptake and awareness of these technologies among the migrant population remain notably low.

Two main technologies developed by private entities to support Nepalese migrants are Shuvayatra and Pardesi. Shuvayatra[64] is a comprehensive safe migration tool that provides vital information on labour rights, work permits, the application process, local dos and don’ts, and working conditions abroad. It also offers country-specific guidance for popular destination countries such as Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar. Shuvayatra designed the application with prospective and returnee male and female labour migrants in Nepal to ensure its relevance and usability.

Pardesi, on the other hand, is a portal that serves as a one-stop information hub for Nepalis seeking foreign employment. It covers a broad spectrum of topics, including financial literacy, remittance utilisation, welfare arrangements, health facilities, etc in various destination countries. It also provides information on the culture, climate, and traffic rules of these countries, helping migrants prepare for their relocation.

Despite the potential benefits of these technologies, their use among migrants, particularly those in the unorganised or informal sectors, appears to be low. This can be primarily attributed to a lack of awareness about these initiatives. Many migrants are either unaware of the existence of such tools or are hesitant to use them due to limited digital literacy and apprehensions about technology.

41. Aapti’s primary research with Nepalese migrants in India

42. Aapti’s primary research with Nepalese migrants in India

43. Aapti’s primary research with Nepalese migrants in India

44. C.A. No. 11928/2016 XIV-A.

51. Aapti’s primary research with Nepalese migrants in India

52. Aapti’s primary research with Nepalese migrants in India

57. Aapti’s primary research with Nepalese migrants in India

Solutions Framework & Recommendations

The challenges faced by Nepalese migrants in accessing and utilising digital services in India highlight a critical need for innovative solutions and collaborative efforts. This section delves into a range of potential solutions and recommendations aimed at addressing these issues. The role of various stakeholders, including government agencies, private sector players, NGOs, and local communities have been addressed to understand how they can contribute to creating a more inclusive and effective technological ecosystem for Nepalese migrants in India. The forthcoming recommendations aim to bridge the gap between policy intentions and practical outcomes, ensuring that Nepalese migrants can fully benefit from the digital services available in India.

Policy Pathways to Integration

Access to any DPI is ultimately governed by policymakers, whose decisions shape the extent and effectiveness of integration efforts. To ensure the successful assimilation of Nepalese migrants into the Indian ecosystem, policy-level changes are imperative. The government must design and implement inclusive systems that facilitate this integration, addressing the specific needs and challenges faced by these migrants.

This section will explore various policy recommendations, ensuring these migrants can fully benefit from the digital services and support mechanisms available in India. By fostering a more inclusive policy environment, the government can help bridge the gap between intention and implementation, paving the way for a more supportive ecosystem for Nepalese migrants.

Outcome indicators for how DPI functions for Nepalese migrants are essential for evaluating the real-world impact of Aadhaar and other digital services. These indicators must be established and meticulously monitored to ensure the intended benefits of DPI are reaching this vulnerable population. Without continuous improvement and adaptation of DPI, the government cannot fully integrate migrants into the country’s socio-economic fabric.

Methods of developing such indicators include tracking quantitative metrics. The number of Nepalese migrants successfully obtaining Aadhaar cards serves as a fundamental indicator of accessibility and outreach effectiveness. These metrics provide insight into the actual utility of Aadhaar for migrants, highlighting areas where the system is functioning well and identifying gaps where improvements are necessary.

It is crucial to assess the socio-economic improvements among migrants resulting from access to DPI. While metrics such as increased financial inclusion, better employment opportunities, and improved access to healthcare can indicate the broader impact of Aadhaar and related digital services, such metrics are generally unavailable for migrants. Implementing these measurements as a general improvement for Aadhaar and DPI will likely yield positive outcomes for migrants. For instance, a rise in the number of migrants with bank accounts or health insurance policies linked to their Aadhaar can demonstrate tangible benefits stemming from digital integration, emphasising the need to scrutinise and enhance existing systems.

In addition to quantitative measures, qualitative assessments offer a nuanced understanding of the migrant experience. Collecting user feedback through surveys and interviews can reveal personal experiences, challenges, and successes that migrants encounter while using DPI. Case studies focusing on individual or community stories can provide rich, contextual insights into how digital services are affecting migrants’ lives. In certain instances, understanding the difficulties faced by migrants in obtaining Aadhaar or hesitancy to use digital services can lead to targeted policy interventions.

By continuously refining and enhancing the existing digital infrastructure based on comprehensive outcome indicators, policymakers can ensure the integration of Nepalese migrants is not only efficient but also equitable. Establishing and monitoring these indicators enables a feedback loop where data-driven insights lead to iterative improvements, ensuring that DPI evolves to meet the changing needs of migrants. This ongoing process of evaluation and enhancement is essential for achieving the full integration of Nepalese migrants into the Indian socio-economic landscape, fulfilling the promises of accessibility and inclusion inherent in the DPI framework.

It is vital to go beyond the implementation of digital public infrastructure and consider holistic approaches that integrate both technological and social welfare systems. While enhancing digital infrastructure through iterative improvements based on outcome indicators ensures efficiency and adaptability, it is equally important to address the socio-economic aspects of integration. Drawing lessons from successful international models can offer valuable learnings. A possible example is in the Philippines’ National Social Security System[63] (SSS) and its AlkanSSSya[64] program.

The SSS system allows migrant workers to pay an enrolment fee and contribute as much as they can into the fund through the AlkanSSSya program. The SSS provides various benefits, including retirement, disability, death, funeral, and maternity benefits, ensuring comprehensive social security coverage for migrant workers. The AlkanSSSya program facilitates easier and more accessible contributions for informal sector workers by allowing small, regular deposits, typically through community-based collection schemes. Through this kind of widespread applicability, and a sustainable model for the program fund, a certain degree of social support can be achieved. As a policy effort by states, such frameworks can increase migrants’ trust in state systems.

There is potential, through policy adoptions and a principle approach to including migrants as valuable communities within a nation - to also provide comprehensive social security coverage, ensuring that Nepalese migrants are not only digitally included but also socially and economically secure. A dual approach of refining digital systems and establishing robust social welfare mechanisms would create a more holistic and sustainable integration model, meeting both the technological and socio-economic needs of migrants.

Digital Integration: Aadhaar Access for Nepalese Migrants

To navigate the Indian system effectively, Nepalese migrants require a technological infrastructure that is accessible. DPI must continually evolve to ensure it remains effective, avoiding obsolescence in the face of changing demands and technological advancements.

A significant aspect of this evolution involves enhancing the offline infrastructure that supports DPI. Despite the digital nature of services, the offline components—such as physical access points, administrative support, and community outreach—play a vital role in ensuring that digital solutions are accessible to all. For instance, setting up more Aadhaar enrolment centres in areas with high migrant populations, and offering assistance through local NGOs can greatly enhance the accessibility and usability of DPI for Nepalese migrants.

The government needs to update and adapt its policies to ensure that Nepalese migrants are explicitly included within the ambit of service delivery associated with Aadhaar. This includes not only recognizing their eligibility for Aadhaar cards but also ensuring they can access the full suite of services linked to Aadhaar. Policymakers must address barriers such as stringent documentation requirements and lack of awareness about the services available to migrants.

The success of DPI in integrating Nepalese migrants hinges on a holistic approach that combines technological innovation with supportive offline infrastructure and inclusive policy updates. By fostering a dynamic, user-centred technological ecosystem and ensuring robust offline support, the government can fulfil the promises made to Nepalese migrants, enabling them to fully participate in and benefit from India’s digital economy.

Bridging Calendars

To address the challenges Nepalese migrants face in obtaining Aadhaar cards, India could consider establishing a system whereby a migrant’s Aadhaar is linked to their Nepalese identity document. One of the primary hurdles in the Aadhaar application process for Nepalese migrants is the difference between the Nepalese calendar (Bikram Sambat) and the Gregorian calendar used in India. This discrepancy often leads to inconsistencies in age and date of birth documentation, complicating the verification process.

Building a system whereby the enrolment centre can directly ensure such conversation between these two calendars, would aid in accurate and consistent documentation for Aadhaar applications. By automatically converting dates from the Nepalese calendar to the Gregorian calendar during the application process, such a system would eliminate a significant barrier and reduce administrative burdens faced by the migrants. Such a platform would drastically reduce the time and effort required for migrants to enrol for Aadhaar demonstrating the potential benefits of a centralised digital system.

Furthermore, implementing a system in India for Nepalese migrants would involve developing a user-friendly digital interface where migrants can input their personal information, including dates in the Nepalese calendar. The system would then automatically convert these dates into the Gregorian calendar format, ensuring consistency across all documents and records. This would not only facilitate smoother Aadhaar card applications but also enhance the overall accuracy and reliability of migrants’ personal data. Such a system could offer additional features tailored to the needs of Nepalese migrants, such as multilingual support, detailed guidelines for the application process, and integration with other essential services like banking and healthcare.

By centralising these services, the platform could provide a one-stop solution for migrants, making it easier for them to navigate the Indian administrative landscape. Such an approach would address a critical barrier, enhance administrative efficiency, and ensure that migrants can fully benefit from the digital services available in India.

Revolutionising remittances through bilateral UPI

The remittance system between India and Nepal offers numerous benefits, serving as a crucial lifeline for many migrant workers. Introducing a bilateral UPI system could make the remittance process smoother for migrants.

The extension of Digital Public Infrastructure such as UPI would be in line with the promises made in the Indo-Nepal treaty as UPI offers near-real-time settlement of payments, reducing processing times and costs associated with traditional remittance methods. This benefits migrants by promoting financial inclusion by encouraging the use of digital payment platforms.

Enabling bi-directional cross-border remittances through UPI would be a significant advance as most remittance systems are currently unidirectional, allowing money to flow from migrant workers to their families. The introduction of bi-directional remittances would allow families to send money to workers in need, creating a more resilient support system within migrant communities. This two-way flow of funds enhances economic stability and empowers migrants and their families to better manage financial challenges.

The introduction of a bilateral UPI system holds immense potential to transform the remittance landscape for India-Nepal migrants. By reducing costs, improving transparency, and enabling bi-directional remittances, this initiative can contribute significantly to the economic well-being and resilience of migrant communities, aligning with broader global efforts to achieve sustainable development and financial inclusion goals.

Designing an inclusive technological ecosystem

Fostering a robust technological ecosystem would aid in innovating technology for Nepalese migrants on a wide scale. It would aid development and deployment of effective digital solutions tailored to the specific needs of the population. There are numerous potential private sector players that could be instrumental in this process, including tech startups, financial technology companies, and social enterprises, each bringing unique capabilities and perspectives.

Local actors and NGOs, often closer to the ground realities, can provide valuable insights and feedback, leading to more user-centric and effective solutions. Local NGOs might identify a specific need for health information among migrants, which can then be addressed by integrating a health information module into an existing digital platform.

To cultivate this ecosystem, it is crucial to encourage public-private partnerships and foster a collaborative environment where various stakeholders can contribute to and benefit from the technological infrastructure. Governments can play a pivotal role by setting regulatory frameworks that promote openness and interoperability, while also providing incentives for private sector participation.

Developing a better technological ecosystem for Nepalese migrants requires a shift towards open standards and collaborative innovation. By breaking down silos and enabling co-creation, it is possible to design digital systems that are more responsive to the needs of migrants. This inclusive approach not only enhances the effectiveness of technological solutions but also ensures that migrants receive the support and resources they need to thrive.

Additionally, the authors examine alternate systems of resilience that can enable the realisation of intended benefits, the potential of community and civil society, and the reimagining of impact and value for Nepalese migrants anchored in their digital and data interactions.

Potential Innovations for connectivity in the Indo-Nepal corridor

There is potential for innovations in the financial corridor between India and Nepal. Technologies such as SympliFi[65] and SentBe[66] exemplify how targeted digital solutions can address the specific challenges faced by migrants. SympliFi, currently operational in the EU-Senegal corridor, enables migrants in another country to act as guarantors for loans in their home country through refundable deposits. This service allows migrants to support their friends and family financially, ensuring they can access loans without traditional hurdles. Implementing a similar service in the Indo-Nepal corridor would provide a vital financial link between Nepalese migrants and their families back home.

SentBe focuses on cross-border money transfers and supports migrants throughout their entire migration lifecycle, including pre-departure, arrival, settlement, re-return, and post-return phases. This approach ensures that migrants have continuous access to essential financial services, enhancing their economic stability and integration into the host country. Adapting a service like SentBe for the Indo-Nepal corridor could significantly streamline remittances and other financial transactions, making it easier for Nepalese migrants to manage their finances efficiently.

Alternatively, a dedicated mobile app or portal could be designed for migrants to provide step-by-step instructions for obtaining an Aadhaar card, accessing healthcare services, or sending remittances, thus bridging the gap between technology and user capability. By leveraging such innovations, stakeholders can develop a robust technological ecosystem that supports Nepalese migrants throughout their migration journey, ensuring they have access to critical financial resources and services. Continuous feedback from the migrant community should inform the ongoing development and refinement of these digital solutions. Establishing channels for user feedback and involving migrants in the design and testing of new features can ensure that the technology evolves in a way that genuinely addresses their needs and challenges.

Bridging the Information Gap

Improving the dissemination of information regarding existing systems is crucial for Nepalese migrants, many of whom rely on informal mechanisms due to a lack of awareness about available technologies. Enhancing their knowledge of these systems is vital for empowering migrants to access essential services efficiently and navigate challenges more effectively. One possible solution is community-based workshops or training sessions conducted by NGOs or local organisations. These workshops can educate migrants about digital platforms, such as Aadhaar enrolment processes, banking services, and healthcare facilities. Providing multilingual resources and tailored guidance can help bridge the language barrier and increase comprehension.

To address these challenges, it is imperative to enhance awareness and education efforts targeted at migrant communities. Outreach programs, community training sessions, and partnerships with local organisations could play a pivotal role in increasing the visibility and usage of these technologies. By bridging the knowledge gap and fostering a more tech-savvy migrant population, these tools can better fulfil their intended purpose of aiding Nepalese migrants in their journeys. Leveraging mobile technology through informative apps or SMS campaigns can deliver targeted information directly to migrants’ devices, ensuring accessibility and convenience.

The Government must use a comprehensive approach involving community engagement, digital tools, and strategic partnerships with private players and local NGOs will significantly improve the knowledge and utilisation of existing systems among Nepalese migrants, fostering empowerment and inclusion in the digital age.

Conclusion

Even though the Indo-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship promises seamless integration, Nepalese migrants in India face significant systemic barriers. Improving access to Aadhaar, enhancing DPI, and ensuring comprehensive policy reforms are essential steps to fulfil this promise. Addressing these challenges will enable Nepalese migrants to fully integrate and benefit from the socio-economic opportunities in India.

This case study highlights the digital and systemic challenges Nepalese migrants encounter while integrating into Indian society. It also shows that DPI has become central to migration policy and requires close and continued attention. Despite the promises of seamless integration made in the Indo-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship, the reality falls short, particularly in the realm of digital public infrastructure. The offline infrastructure fails to support the efficient use of Aadhaar and other digital services, leaving many migrants without access to crucial resources. This digital divide exacerbates their marginalisation, preventing them from fully participating in the socio-economic fabric of India.

For effective assimilation of migrants into the host country, several factors must be considered. Firstly, there needs to be a robust awareness campaign to educate migrants about available digital tools and services. Secondly, the digital infrastructure must be inclusive and user-friendly, catering to the specific needs of migrants. Thirdly, policies should be reformed to ensure that migrants can access these services without bureaucratic hindrances. Finally, there should be continuous monitoring and evaluation of the DPI’s effectiveness in meeting the needs of migrants, with a focus on real-world outcomes and user feedback. Addressing these aspects will help bridge the gap between policy promises and practical realities, fostering a more inclusive environment for Nepalese migrants in India.

Integrating Nepalese migrants into India's social welfare infrastructure requires a multi-faceted approach that ensures both the digital and offline systems are equipped to handle their specific needs. The offline infrastructure, including local government offices, health services, and community centres, must be made aware of the intricacies involved in the integration process. Training sessions and awareness programs for officials and workers in these offline systems can help them understand the unique challenges faced by migrants and the specific documentation they might need to access services. This will ensure that migrants are not turned away due to misunderstandings or lack of knowledge.

Policy design must be inherently inclusive, accommodating diverse needs and ensuring practical implementation for accessibility. Policymakers can create a more inclusive environment that does not inadvertently exclude migrants from accessing essential services, thereby fulfilling the promises of integration and support made in international treaties.

Ensuring safeguards in digital public infrastructure is crucial to promoting inclusion and minimising harm, particularly when implementing interoperability between systems. Interoperability allows different systems to work together seamlessly, but it also poses risks if not properly managed. Safeguards such as robust data protection measures, clear guidelines on data sharing, and stringent access controls must be implemented. These measures help protect migrants’ personal information and ensure that it is used only for intended purposes, reducing the risk of misuse and exclusion.

Involving the community in this process is essential. Engaging migrants and community organisations in discussions about the implementation of DPI ensures that they are informed about the potential risks and benefits. This participatory approach helps build trust and allows migrants to voice their concerns and provide feedback on the systems being developed. Community involvement also fosters a sense of ownership and accountability, making it more likely that the systems will be used effectively and responsibly. Educational programs and workshops can be organised to raise awareness about the potential repercussions of data misuse and the steps that can be taken to prevent it. By incorporating community input and maintaining transparency, policymakers can create a more inclusive and secure digital ecosystem for Nepalese migrants in India.

7. https://doi.org/10.7939/r3-ae4d-pq06

8. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-92377-8_11

9. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/598086a0ed915d022b00003c/K4D_HDR__Migration_and_Education.pdf

10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3648681/

11. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-92377-8_11

12. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/nri/work/immigration-wrap-2023-the-world-wants-more-foreign-workers-but-only-the-highly-skilled-ones/articleshow/106294047.cms?from=mdr

13. https://era.library.ualberta.ca/items/6f7244ed-0573-4b5a-8054-876b16b2909f

14. http://data.uis.unesco.org/215. http://data.uis.unesco.org/2

16. http://data.uis.unesco.org/

17. http://data.uis.unesco.org/

18. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-92377-8_4

19. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-92377-8_420. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-92377-8_3

21. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-92377-8_5

22. https://ojs.library.queensu.ca/index.php/surveillance-and-society/article/view/16105

23. https://epic.org/issues/surveillance-oversight/border-surveillance/

24. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/04/population-ageing-and-immigration-germanys-demographic-question/

25. https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/pressemitteilungen/EN/2022/12/migration_agreement.html

26. DAAD India. “Indian Student Numbers Touch a Record High in Germany,” August 11, 2023. https://www.daad.in/en/2023/08/11/indian-student-numbers-touch-a-record-high-in-germany/

27. DAAD India. “Indian Student Numbers Touch a Record High in Germany,” August 11, 2023. https://www.daad.in/en/2023/08/11/indian-student-numbers-touch-a-record-high-in-germany/

28. https://gdpr-info.eu/

29. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20230601STO93804/eu-ai-act-first-regulation-on-artificial-intelligence

30. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_24_1970

31. https://eulisa.europa.eu/About-Us/Organisation/Eurodac-Advisory-Group

32. https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/agencies_en#ecl-inpage-789

34. https://travel-europe.europa.eu/ees_en34. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358531118_Higher_education_institutions_as_eyes_of_the_state_Canada's_international_student_compliance_regime

35. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358531118_Higher_education_institutions_as_eyes_of_the_state_Canada's_international_student_compliance_regime

36. Cranston, S. & Esson, J. (2024) Producing international students: Migration management and the making of population categories. The Geographical Journal, 00, e12582. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12582

37. Cranston, S. & Esson, J. (2024) Producing international students: Migration management and the making of population categories. The Geographical Journal, 00, e12582. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12582

38. Cranston, S. & Esson, J. (2024) Producing international students: Migration management and the making of population categories. The Geographical Journal, 00, e12582. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12582

39. Salter, M. B. (2006). The Global Visa Regime and the Political Technologies of the International Self: Borders, Bodies, Biopolitics. Alternatives, 31(2), 167-189. https://doi.org/10.1177/030437540603100203

40. Cranston, S. & Esson, J. (2024) Producing international students: Migration management and the making of population categories. The Geographical Journal, 00, e12582. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12582

41. Cranston, S. & Esson, J. (2024) Producing international students: Migration management and the making of population categories. The Geographical Journal, 00, e12582. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.1258242. www.daad.de. “Data Privacy Statement,” n.d. https://www.daad.de/en/data-privacy-statement/

43. “Privacy Policy | Uni-Assist,” n.d. https://www.uni-assist.de/en/privacy-policy/

44. https://www.goethe.de/ins/in/en/dat.html

45. “ETS Privacy and Security Policy | Legal,” n.d. https://www.ets.org/legal/privacy.html#accordion-1f944a369f-item-abeeb9a313

46. https://passportindia.gov.in/AppOnlineProject/onlineHtml/privacyPolicy.html47.European Commission. “Privacy Policy for Websites Managed by the European Commission,” n.d. https://commission.europa.eu/privacy-policy-websites-managed-european-commission_en#where-to-find-more-detailed-information

48. Our Data Our Selves. “Booking Flights: Our Data Flies with Us,” n.d. https://ourdataourselves.tacticaltech.org/posts/50-booking-flights/#:~:text=If%20we%20use%20the%20same,through%20different%20channels%20over%20time

49. FRANKFURT.DE - DAS OFFIZIELLE STADTPORTAL. “Datenschutzinformationen Der Offiziellen Webseite Der Stadt Frankfurt Am Main,” n.d. https://frankfurt.de/datenschutz

50. Data Protection - GERMAN STUDENT INSURANCE | GERMAN STUDENT INSURANCE,” n.d. https://www.german-student-insurance.com/en/data_protection

51. Deutsche Bank. “Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions,” October 5, 2023. https://www.deutschebank.co.in/en/disclaimer.html#parsys-columncontrol_copy_c-columnControlCol1Parsys-accordion_copy-accordionParsys-accordionentry_1378870526

52. Ag, Deutsche Telekom. “Data Privacy Information.” Deutsche Telekom, August 22, 2023. https://www.telekom.com/en/deutsche-telekom/data-privacy-information-1744

53. Jayadeva Interview

54. Jayadeva, Sazana. “Keep Calm and Apply to Germany: How Online Communities Mediate Transnational Student Mobility from India to Germany.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46, no. 11 (2020): 2240–57. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1643230

55. Jayadeva, Sazana. “Keep Calm and Apply to Germany: How Online Communities Mediate Transnational Student Mobility from India to Germany.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46, no. 11 (2020): 2240–57. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1643230

56. Jayadeva, Sazana. “Keep Calm and Apply to Germany: How Online Communities Mediate Transnational Student Mobility from India to Germany.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46, no. 11 (2020): 2240–57. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1643230

57. Jayadeva Interview

58. Taylor, Linnet, and Dennis Broeders. “In the Name of Development: Power, Profit and the Datafication of the Global South.” Geoforum 64 (August 2015): 229–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.07.002

59. Taylor, Linnet, and Dennis Broeders. “In the Name of Development: Power, Profit and the Datafication of the Global South.” Geoforum 64 (August 2015): 229–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.07.002

60. Taylor, Linnet, and Dennis Broeders. “In the Name of Development: Power, Profit and the Datafication of the Global South.” Geoforum 64 (August 2015): 229–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.07.00261. Chang, Shanton. (2017). Digital Journeys: A Perspective on Understanding the Digital Experiences of International Students. Journal of International Students. 7. 347-366. 10.32674/jis.v7i2.385

62. Chang, Shanton. (2017). Digital Journeys: A Perspective on Understanding the Digital Experiences of International Students. Journal of International Students. 7. 347-366. 10.32674/jis.v7i2.38563. https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/schengen-borders-and-visa/visa-information-system_en

64. https://cpg-online.de/integrating-technology-the-first-step-towards-theorizing-the-role-of-border-surveillance-in-the-european-border-regime-and-its-relationship-to-european-integration-theory/

65. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_1262

66. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_1262

67. https://picum.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/INFOGRAPHIC.-Interoperability-Systems-and-Access-to-Data_WEB_RGB.pdf

68. Salter, M. B. (2006). The Global Visa Regime and the Political Technologies of the International Self: Borders, Bodies, Biopolitics. Alternatives, 31(2), 167-189. https://doi.org/10.1177/030437540603100203

69. Salter, M. B. (2006). The Global Visa Regime and the Political Technologies of the International Self: Borders, Bodies, Biopolitics. Alternatives, 31(2), 167-189. https://doi.org/10.1177/030437540603100203

70. Salter, M. B. (2006). The Global Visa Regime and the Political Technologies of the International Self: Borders, Bodies, Biopolitics. Alternatives, 31(2), 167-189. https://doi.org/10.1177/030437540603100203